As we approach the end of the year, Congress is under heavy pressure to agree on a new stimulus package before they recess for the year this Friday.

To date, there are several packages being proposed, none of which as gargantuan as the stimulus passed earlier this year.

The United States finds itself in a precarious position. Delay stimulus, and face the sheer drop of an economic cliff, or push stimulus through, only to deal with a complicated, inflationary economy later.

In either case, we the people are left to wonder what the heck can be done to put ourselves in any semblance of a defensible position.

The answer?

Hedging.

Stimulus Packages

In the final week before Congress gives their weary fingers a break from pointing, one aid package has emerged as the front runner.

Size: $908 billion

Terms: This bipartisan proposal would exclude direct stimulus payments, and instead focus on unemployment relief payments, totalling in $300 additional, weekly payments.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin also proposed a stimulus package, which was met with less enthusiasm.

Size: $916 billion

Terms: $600 stimulus payments to each qualifying citizen, but considerably less unemployment relief.

As of the 14th, the bipartisan coalition I mentioned above detailed a legislative plan for the $908 billion package, which will in fact be split into two separate bills.

Bill 1: $784 billion relief package that will focus efforts on paycheck protection and unemployment, among other provisions.

Bill 2: $160 billion earmarked for state and local governments. For what? That’s currently unclear.

Current unemployment relief and eviction protection is set to expire before the end of the year, making the timing of forthcoming aid paramount. As California once again enters into lockdown and cities across the country begin to tighten restrictions, unemployment numbers are certain to rise once more.

Money Printing and Inflation

As you may have guessed from the beginning of this article, I planned to write about how the next stimulus package would engender widespread inflation, devaluing the dollar and thus making gold an attractive hedge against volatility.

However, in the course of my research to create a half-cogent article, I encountered some confounding contradictions.

For example, if “printing money”--which we’ll refer to as “increasing the money supply” henceforth--directly correlates to inflation, why were the years after the 2008 financial crisis not characterized by a ballooning economy?

Starting in 2008, the Central Bank increased the money supply by some $4.5 trillion through various quantitative easings. And look, inflation barely got above 3%:

It turns out that there are a number of scenarios where increasing the money supply does not correlate to rising inflation.

Let’s begin by understanding the commonly accepted cause of inflation.

Increased Money Supply = Increased Inflation

The basic theory states that if the money supply increases faster than the real output of an economy--all other things remaining equal--inflation will occur. Key words obviously being, “all other things remaining equal.”

Various Google searches for why increasing the money supply causes inflation produced banal examples where increasing the money supply correspondingly increases the price level of goods and services.

But...why?

I had to dig a little deeper.

Economists came up with a simple formula to represent inflation, called the Quantity Theory of Money. The formula is written as MV = PY, where

M = Money supply

V = Velocity of circulation (how many times money changes hands)

P = Price level of goods and services

Y = National income

The formula relies on assumption. Specifically, the assumption that the velocity of circulation and national income stay constant in the short term.

If we assume that V and Y are constant, then yes, an increase in M begets an increase in P.

That, however, is the problem with assuming. You’re usually wrong. Especially in a pandemic-induced recession.

Velocity of Circulation

The Quantity Theory of Money also assumes the fact that having more money equates to more spending. Since the money supply has increased, it’s reasonable to assume that there’s more money in American’s pockets, and likewise reasonable to assume they’re slingin more greenbacks.

While this may generally be true, the pandemic has seen Americans do anything but that.

Statista conducted a survey of personal saving rates across the US for 2020.

The personal saving rate is calculated as the ratio of personal saving to disposable personal income.

As you can see, personal saving rates soared from March to June, the months of heaviest stimulus payments. Even in September and October, saving rates were nearly twice as high as the average from 2015 through 2020.

In this instance, an increase in money supply correlated not to an increase in the velocity of circulation, but a drastic decrease. This trend began a deflationary movement in the economy which was only buoyed by relaxed lockdowns across the nation that created more places for money to circulate.

Liquidity Traps

Another scenario where increasing the money supply does not correlate to inflation comes from the Keynsian view of economics.

The basic premise of this view is that in a recession, there is excess capacity in the economy due to unemployment, lower GDP, etc. As such, increasing the money supply only serves to fill in this capacity, and does not cause inflation.

In a recession, the central bank will typically lower interest rates to incentivize borrowing and spending, as debt is cheaper. The general idea here is that if debt is more liquid, spending will increase.

In many cases, this is true. However, like we saw above in the case of personal saving rates, this is not the case for the global pandemic.

Lowered interest rates did not incentivize spending. Americans continued to save more than ever, which provoked deflation as the velocity of circulation slowed. Increasing the money supply here again does not cause inflation.

Hedging?

While the dollar could be devalued through a number of other factors, it’s unlikely to be through inflation.

As much as I harp on the inefficacy of Congress and the Central Bank, they have learned a few lessons from history. While increasing the money supply can be an inflationary action in many situations, there are deflationary measures the Fed can take to combat this.

I wrote about this in a previous article, found here.

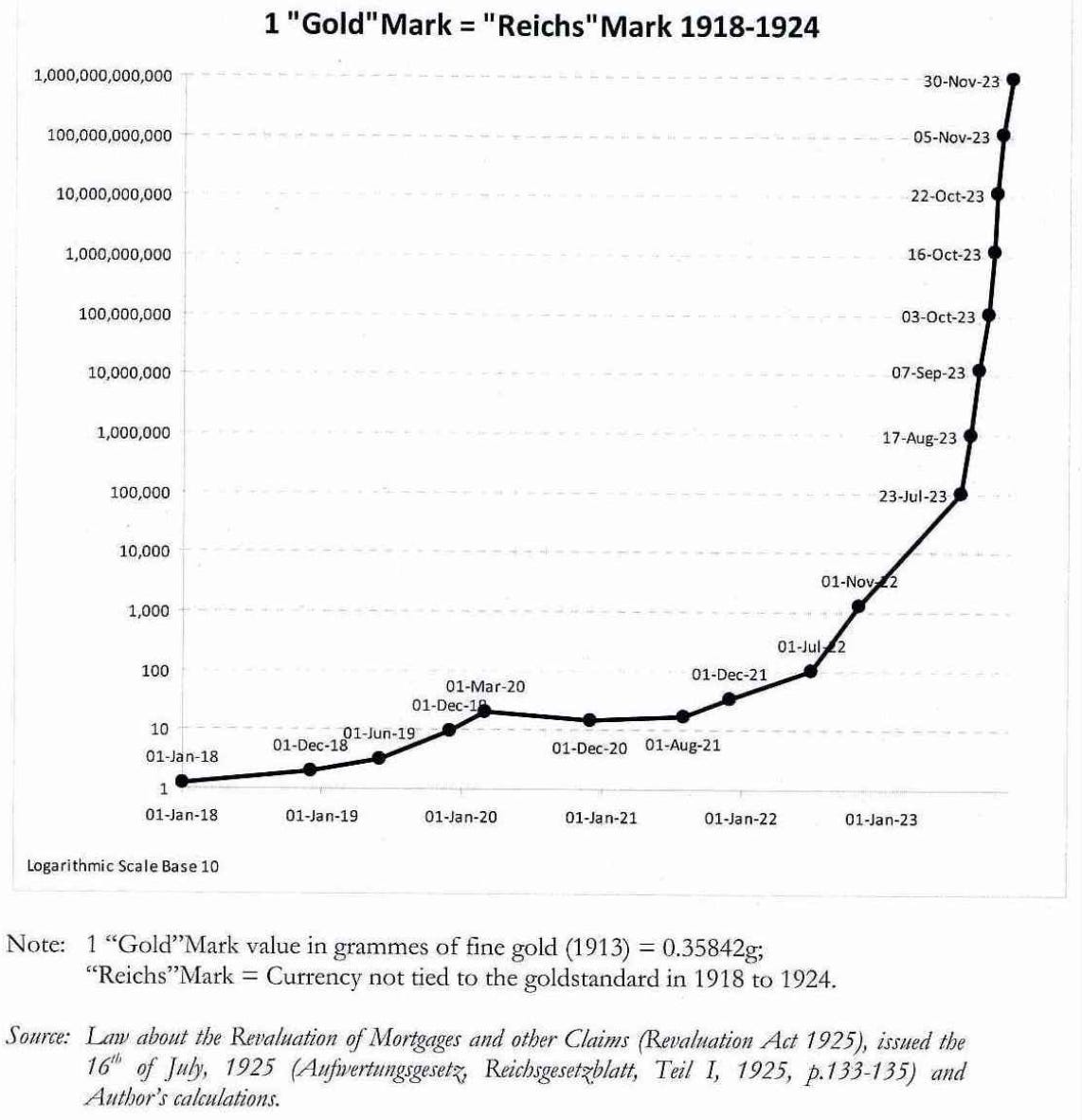

Balancing inflationary and deflationary measures was a skill yet unknown to the economists of the Weimar Republic, which is often cited as the worst case of hyperinflation in history.

Over the course of a two year period, the Weimar Republic reached a monthly inflation rate of 29,500%. Under these rates, it took approximately 3.7 days for prices to double.

At its worst, one U.S. dollar was worth 4,210,500,000,000 German marks. At this point, the cost of printing German marks was more than the value of the mark itself. Children made kites out of marks, since it was more readily available and less valuable than normal paper.

There are many contributing factors to the economic disaster of the Weimar Republic, many of which we are not currently experiencing in the United States.

Given the saving-heavy nature of this pandemic, I think it unlikely that we will deal with high levels of inflation moving forward. This is the major factor of currency devaluation, and without it, I think the dollar will continue to maintain its position as the world’s majority reserve currency for some time.

Seeing this, I’m unlikely to hedge my investments with gold, but having a small holding was never a bad idea from a diversification and risk standpoint.

That being said, I’ve been wrong before. None of this is meant to be professional advice, only education, entertainment, and my incessant tangents.

As always, thanks for reading.

(P.S. - I may forego an article or two for the holidays. Gotta celebrate the ol’ yule.)

You have a typo in this statement

If we assume that V and Y are constant, then yes, an increase in M begets an increase in Y. Shouldn't that be an increase in P?