In the past 23 US Presidential elections, 19 resulted in positive gains for the stock market. The four outlying elections were marked by a common thread, which may feel familiar…

But first! There’s a kind old man named Ray Dalio who demands our attention. Evoking feelings of an affable grandfather, Mr. Dalio looks like he could make you a mean stack of pancakes and say something in passing that fundamentally changes the way you see the world.

In fact, he runs the largest hedge fund in the world, Bridgewater Associates, with something like $130 billion under management. (Pancake making skills are TBD.)

While obviously being wicked smaht, Mr. Dalio is also aware of his increasing age. Like any good grandfather would do, he’s spent the last several years compiling his accumulated knowledge of the world, translating it into the language of us plebeians, and gifting it to the world.

Today, Grandpa Ray is going to teach us how the economy works.

For those who want it straight from the horse’s mouth, find his original video here. We’re going to do a brief synopsis, and then see where the current economy stacks up in a typical economic cycle.

How The Economic Machine Works

An economy, like most things, can be broken down to its component parts, making it simpler to understand. The basic building block of any economy is a transaction.

We make transactions all the time. Each time you buy or sell something, you create a transaction. So, a transaction consists of a buyer exchanging money or credit with a seller for goods or services.

Transactions drive the entire economic machine, so if we can understand transactions, we can understand the whole shebang. Since transactions are requisite on spending, we can even say that spending is the driver of the economy.

Thus, shrinking spending and an economic contraction of 31.9% over the course of the Coronavirus lockdowns makes a ton of sense.

Businesses and governments also engage in transactions in the same way. In fact, the largest buyer and seller in the US economy is the government itself.

The government can be broken down into two parts: the central government, which spends money and collects taxes, and the central bank, which operates differently than other buyers and sellers.

Why? Because the central bank controls the amount of money and credit in the economy. Of these factors, credit is the most important. Credit plays an enormous role in the economy, and the creation of economic cycles.

Credit

Credit is created between lenders and borrowers. When you use your credit card, the bank behind your card essentially lends you the money to complete a purchase, which you will pay back later.

Fun Fact: Within the US economy, there’s approximately $55 trillion of credit, but only ~$3 trillion in hard cash.

Credit helps both lenders and borrowers get what they want. Borrowers agree to pay back the principal of the credit, as well as interest, in order to buy a house or car, and lenders collect their original money back, plus more.

This is the first step of the economic cycle. When a borrower is given credit, he is able to increase his spending, and spending drives the economy. One person’s spending becomes another person’s income. So, the more you spend, the more others earn.

When someone’s income rises, lenders are more willing to lend them credit. Those people then borrow on favorable terms, and a cycle is created.

The more this borrowing cycle repeats itself, the more credit is created. Credit creates buying power, but it also creates debt, since the credit must be paid back.

As credit is created, spending increases, incomes increase, and more borrowing occurs. When the amount of spending and income grow faster than the production of goods, prices rise. Since incomes can rise so quickly when lending is widespread, this is a normal part of any economy. When prices continue to rise, this is called inflation.

The central bank, however, doesn’t want too much inflation. Too much inflation devalues our own currency, which leads to widespread problems down the road. Thus, seeing prices rise, the central bank raises interest rates on credit.

This makes borrowing more expensive. Instead of paying back the principal and 2% interest over the duration of the repayment, borrowers now have to face a 5% interest rate, which drastically increases the amount of money repaid in the long run.

Now, fewer people can afford to borrow money, and any existing debt they have becomes more expensive. Money is diverted from spending towards paying off loans, and outward spending decreases. Thus, the economy slows.

What goes up, must come down. This is called the short term debt cycle.

Long Term Debt Cycle

When inflation has decreased but spending is also continuing to decrease, the central bank lowers interest rates again. Lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper, and spending increases, galvanizing the economy into another upward swing.

Now, this is a relatively closed system. Environmental factors like emotion, greed, and fear have not yet been fuel injected into the economic engine.

Take greed, for example. In an economic upswing, borrowing is cheap, people get greedy and acquire more things, and generally feel wealthy. The amount of spending increases, but so does the amount of debt.

With each consecutive borrowing cycle, because of humanity’s innate tendency to be greedy, the amount of spending and debt is greater than that of the last cycle.

This cycle continues, but eventually, the amount of debt surpasses the amount of income and spending. The debt burden, or the ratio of debt to income, becomes too great for the economy to bear. People are forced to cut back their spending due to the growth of their debt, and thus incomes decrease, borrowers are less creditworthy, and lending slows.

Debt continues to rise, spending decreases further, and the cycle reverses itself. The United States and much of the world saw this happen in 2008.

Deleveraging

When this cycle of debt reverses, we enter a period of deleveraging. Deleveraging is marked by further cuts to spending and incomes, credit reduction, asset price drops, the stock market crashing, and social tensions rising. Sound familiar?

Even worse, this becomes its own vicious, downward cycle.

Woof. If your head is spinning, so is mine.

And yes, I’ll be doing my best to get Matthew McConaughey in here whenever appropriate. Or inappropriate.

So Now What?

To restimulate the economy, the central bank typically lowers interest rates to incentivize borrowing. However, in a deleveraging, interest rates are already 0% or close to it, so this is no longer an effective tactic.

Interest rates dropped to 0% during the 1930s, as well as in 2008, and as you can imagine, that’s a dicey place to be. At this point, the debt burden has risen too high to be massaged and reduced by lowering interest rates.

So what’s a guy supposed to do?

At this point, there’s basically four options.

People, businesses, and governments reduce spending.

Word. They do this, but since a reduction in spending becomes a reduction in someone else’s income, all this does is further increase the debt burden. Oops.

Debts are reduced through defaults and restructuring.

i.e. The Big Short

Unable to repay debt, defaults are taken, assets are lost, banks might crash and need to be bailed out, but technically, debt has been reduced.

Restructuring entails creating new terms for a loan. This means the lender could be paid back less than the original principal, the interest rate is lowered, or the duration to pay back the loan is increased.

This helps to reduce some debt, but doesn’t fix the economy yet.

Wealth is redistributed from the have’s to the have not’s

You guessed it — taxes.

The central government raises taxes on the wealthy to redistribute money to the lower income classes.

People are a huge fan of this and it isn’t controversial at all.

And lastly, the central bank prints money.

Each of these four options is used in moderation, believe it or not. If you just popped a blood vessel from internally screaming about how the government only ever prints money and the nation is doomed — sorry :)

Rebalancing the Economy

The central bank and government work together to coordinate deflationary and inflationary measures of rebalancing the economy.

Printing money is an inflationary measure. Reduced spending, debt defaults, and wealth redistribution are all deflationary.

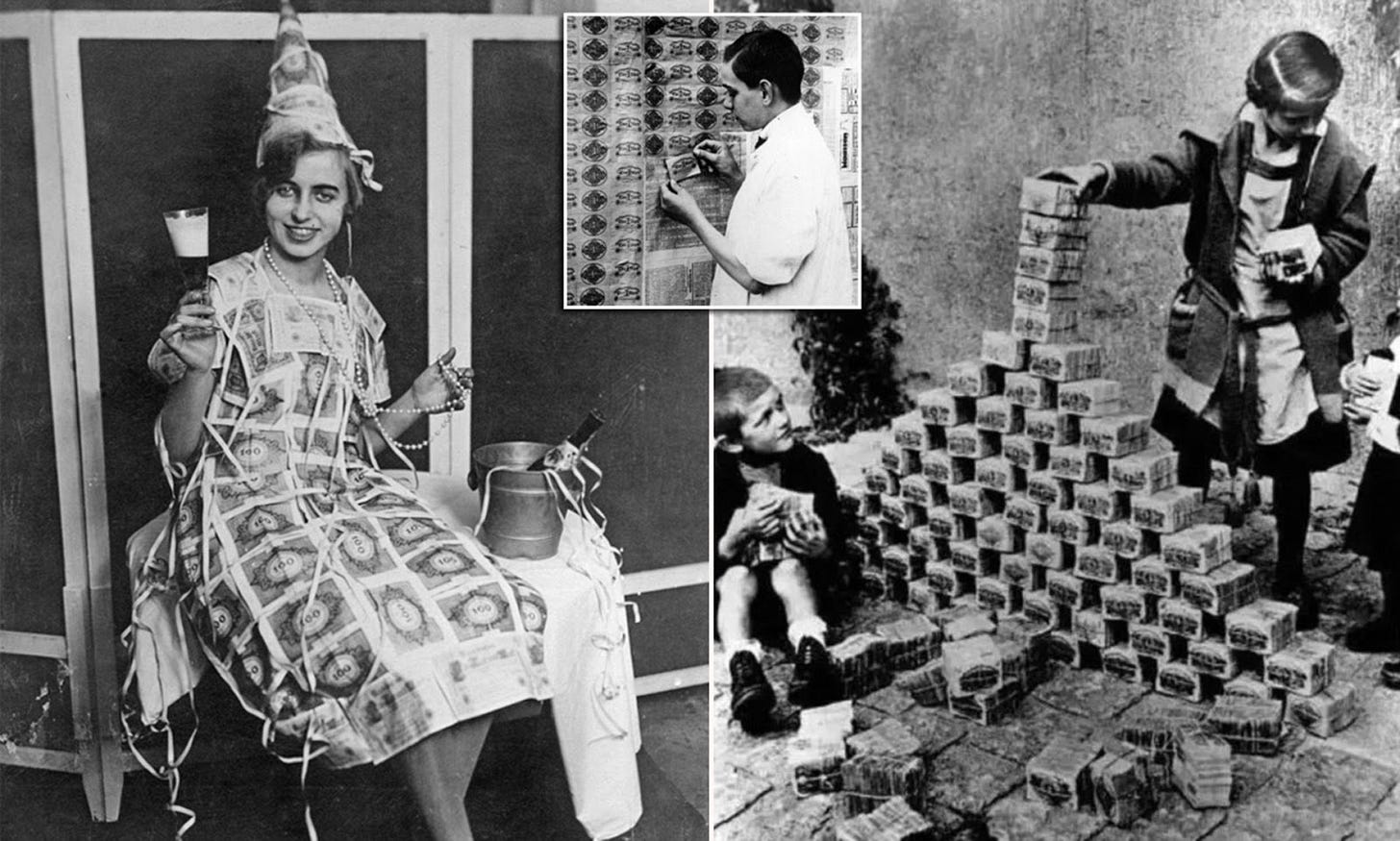

If the central bank only printed money, you’re right, inflation would increase, and we’d start to look like Germany in 1923. So hyperinflated you could build a tower with your useless cash. Or sew a dress. Or make a dunce hat.

Fun Fact: At the height of Germany’s hyperinflation crisis, 4.2 trillion German marks were worth just 1 American dollar.

Back to the point, take the current global pandemic. With record unemployment rates and spending being crushed, the US economy was already spiraling down a deflationary hole. This led to debt defaults and restructuring, which pushed more deflationary pressure onto the back of the economy.

So, the central bank responded with an inflationary measure - printing money. The stimulus packages got money into the hands of the spending-averse American populace to encourage cash expenditures, which would therefore increase other’s incomes and stimulate the economy as a whole.

In fact, inflation hasn’t been an issue at all in 2020. Check out this article, and the chart below:

As you can see, inflation was actually highest in January of 2020. Shrinking spending and debt defaults caused deflation through May, and then the stimulus packages pumped some juice back into the system through August, and likely September.

While this has helped to buoy the sinking economy, it doesn’t mean we’re out of deep water yet. An article by Forbes took a look at how Americans have been spending their stimulus checks.

The issue is that only ~50% of Americans have actually been spending them. The other half has decided to save the money for further future uncertainty, or paying down existing debts.

In my opinion, this is a zero sum situation. The amount of spending reintroduced to the economy is not enough to combat the still rising debt burden, which will continue to push us further into a recession.

So, Where are We Headed?

Frankly, I don’t really know. The stock market refuses to acknowledge the financial reality of America, and for all I know, it may continue to do so.

However, as I mentioned before, of the 23 last Presidential elections, 19 resulted in net gains across the stock market. What about those 4 that didn’t, though?

Those 4 election years were severely impacted by major macroeconomic events.

1932: The Great Depression

1940: WWII

2000: The tech bubble

2008: The financial crisis

2020: The global pandemic?

If the election, social unrest, pandemic, and GDP contraction can shake the stock market in these next few months, it’s my opinion that the US economy will enter a period of deleveraging. We’re not there yet, but we’re close.

Throw in the bank crisis I wrote about last week, and things look even less fun.

I apologize profusely for the gargantuan length of this week’s article. Grandpa Ray just has a lot of wisdom to diffuse.

If you’ve made it this far, what do you think? Is another economic crash inevitable? Am I a dunce and completely off my rocker? Does Grandpa Ray have no idea what he’s talking about?

Comment below!

Thanks for reading :)